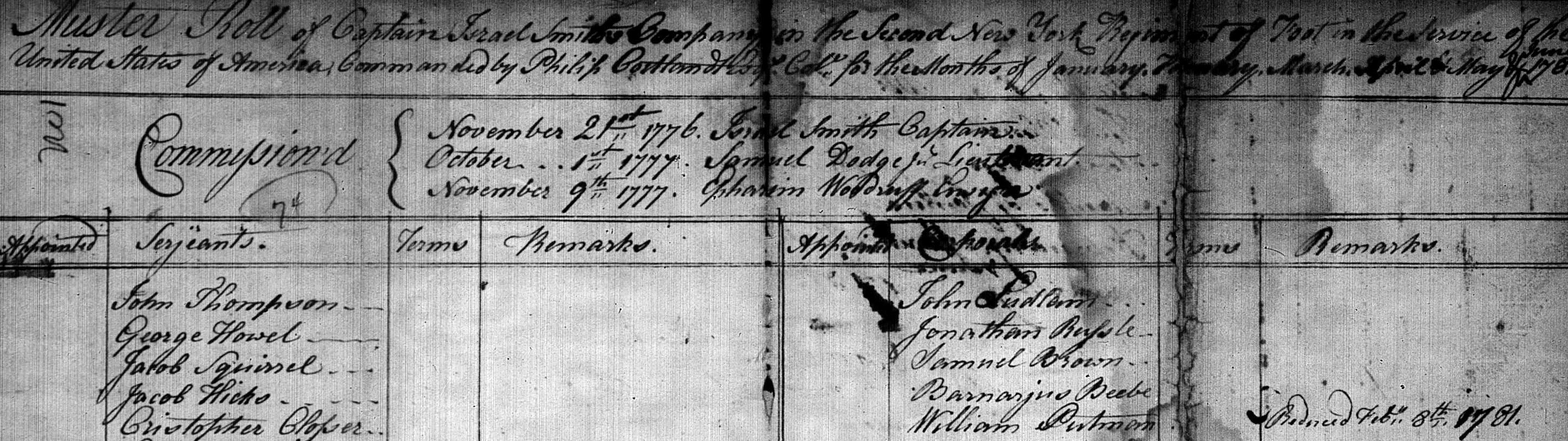

[caption id="attachment_8303" align="alignnone" width="800"]

Großbritannien:

Kinder polnischer Juden aus dem Gebiet zwischen Deutschland und Polen bei Ihrer Ankunft mit der "Warschau" in London.

Aufn. Februar 1939[/caption]By Rachel SilvermanThe status of Jews in pre-WWI eastern Europe is a rather disheartening subject, so I’d like to preface with this caveat: The history and causes of anti-Semitism in Europe – especially in the eastern bloc – span centuries, are vastly complex, and warrant deeper analysis than I offer in this modest blog post. However, understanding the social and political environment in which our Jewish ancestors lived can be very helpful in informing our search for documentary evidence.

Origins

Our story begins in 1772 with the First Partition of Poland, in which Russia gained a region known as “White Russia” (modern-day Belarus) and Latvian-Lithuanian area east Dvina and Dnieper rivers. At that time, Russia was ruled by Empress Catherine II (1729-1796), also known as Catherine the Great. The process of adapting Russian laws to encompass the inhabitants of the newly annexed areas hit a snag when it came to the Jews living in the former Polish regions – a massive population whose ancestors had been barred or expelled from Russia and her territories, in whole or in part, on at least six separate occasions between 1649 and 1742.

Timeline of Events

Events which directly impacted the Jewish population are in boldface. Pay special attention to rules, laws, and regulations which required paperwork or could have yielded related documentation! A couple of these examples and where to search documents are in red.

1791

Establishment of the Russian Pale of Settlement / Jews are forbidden access to trade guilds outside the Pale

Pushed by popular opinion among Russian trade guilds, especially in Moscow, Catherine II issues an edict outlining sweeping restrictions on Jewish residency, movement, property, and trade.

The area to which Jewish subjects are limited becomes known as the Pale of Settlement. According to Catherine II’s Law on the Settlement and Migration of Jews in the Russia Empire, Jews are only permitted to live and conduct business within the Pale—with a few exceptions—which is comprised of annexed territories from Poland and those areas taken from Turkey. Jews are forbidden from traveling outside the Pale without an “exit permit.”

1793

The Second Partition of Poland increases Russia’s territory, but adds to the “problem.”

1794

Catherine II levies doubled taxes on Jews registered in trade guilds

1795

The Third (and final) Partition of Poland completes Russia’s Pale of Settlement, which ends up stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea; covering much of modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, and Lithuania.

1796

Death of Catherine the Great; ascension of her son, Paul I

1801

Death of Paul I (assassinated); ascension of Paul I’s 24-year-old son, Alexander I

1804

Enactment of the Statute Concerning the Organization of the Jews by Alexander I

This sweeping regulatory document contains new laws that touch on every aspect of Jewish life in the Russian Empire. The Tsar, viewing himself as “enlightened,” aims to “correct” his Jewish subjects’ way of life through a mixture of new restrictions and privileges specific to the Jewish population. His end-goal is to bring about the “education” (i.e. assimilation) of Jews into the Russian populace, but to do so in a way that is economically advantageous only to “the native population of those Governments in which these people are allowed to live.”

Many of today’s descendants of Ashkenazi Jews can trace their family lines back to the generation who lived at the time of Alexander I’s all-encompassing Statute, which required Jews in the Russian Empire to adopt permanent, inheritable surnames, instead of using Yiddish (and Russian) patronyms.

1807/1808

Jews are no longer permitted to reside in villages or small towns, as a part of the 1804 Statute. This undermining of village economies is no less than catastrophic, for Jews and Gentiles alike.

1815

The Congress of Vienna

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the victorious nations convene and divvy up the lands of the conquered. The Russian Empire is handed control of the Kingdom of Poland, which is also known as Congress Poland. Although no longer independent, Poland is allowed to exist as a semi-autonomous state, with its own constitution and a separate government.

Jews in Congress Poland are not subject to anti-Jewish laws meant for the Pale of Settlement, but they are well within the grasp of the Tsar. The constitution allows Alexander I to appoint a Namiestnik (Pol: “viceroy”) from among his nobles, to act as deputy over the Kingdom.

Almost immediately, Christian residents of Warsaw appeal to Namiestnik Jozef Zajaczek to re-implement a policy of segregation for Jewish inhabitants, originally enacted in 1809 by Duke Frederick Augustus I of Warsaw (but allowed to expire).

1821

Tsar Alexander I re-enacts segregation measures and further restricts Jews from specific areas in Warsaw. These measures are soon enforced in towns and cities across Congress Poland, leading to the necessary formation of "Jewish quarters" (and sometimes ghettos).

1825

Death of Alexander I; ascension of his son, Nicholas I (1825-55)

Under Nicholas I, state-sponsored persecution of Jewish inhabitants becomes the status quo. The Tsar’s official policy is “to diminish the number of Jews in the empire,” as stated in one official document. His edicts, which are aimed specifically at the Jewish population, clearly outline his deep resentment for those Jews living under his rule.

1827

In the Pale: Implementation of compulsory military service for Jewish males (also known as conscription or the draft)

Conscription is one of the many tools used by Nicholas I to reduce the Jewish population. From the age of 12 to 25, all Jewish men and boys are targets of conscription. They are to serve for a duration of no less than 25 years. The Tsar endorses proselytization for adult soldiers and harsh living conditions for the unbaptized, occasional forced baptism of child recruits (called “cantonists”).

While the gentile populace has been subject to conscription for decades, Jews have historically been exempt from service for various reason. The Tsar places a recruit quota on Jewish communities in the Pale that far surpasses that of the gentile population.

Fearing the loss of their lives and cultural heritage, able-bodied Jewish men and boys flee the Pale en masse for Congress Poland and parts beyond. Jewish community leaders, held personally liable for implementing the new law, scramble to meet the harsh conscript quotas, dreading even harsher penalties should they fail to provide enough soldiers to the Tsar.

The poorest Jewish families are terrorized by the presence of khapers (Yiddish: "grabbers"), community members tasked by shtetl leaders with kidnapping the children of their poorest inhabitants--sometimes as young as 8 years old--to satisfy the Tsar's requirements.

1832

The Kingdom of Poland loses semi-autonomy as a result of the November Uprising. Tsar Nicholas I abolishes the Polish constitution, army, and legislative assembly.

1835

Hebrew and Yiddish are banned in public

Travel and settlement are further restricted within the Pale

1843

Jews in the Kingdom of Poland are impressed into compulsory military service, albeit with relatively fewer dramatic requirements.

1844

Creation of Russian state-run Jewish schools within the Pale, with both Christian and Jewish teachers, aimed at assimilating the Jewish population:

"...the purpose of the education of the Jews is to bring them nearer to the Christians and to uproot their harmful beliefs which are influenced by the Talmud." (The Huddled Masses: Jewish History in the Former Soviet Union: First-hand interviews with the Émigrés)

Establishment of “candle tax” to maintain aforementioned schools – Candle Tax lists searchable on JewishGen.org

Image credit: Jewish Virtual Library, "Modern Jewish History: The Pale of Settlement” (http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/History/pale.html).

1845

Traditional Jewish clothing and peyot (men’s "sidelocks") completely banned in the Pale of Settlement

1846-1850

Traditional Jewish clothing gradually outlawed in the Kingdom of Poland

1855

Death of Nicholas I; ascension of his son, Alexander II

1856

Alexander II abolishes conscription of Jewish children

1857-1881

Period of relative peace for Jewish subjects; Emancipation of Russian serfs in 1861

1881

Assassination of Alexander II

Although carried out by Russian revolutionaries, some place blame for the Tsar’s death on Jews in the Pale. A wave of anti-Jewish riots, called pogroms, ensues. Over the course of the next three years, over 200 pogroms occur in the Russian Empire.

1882

The May Laws are enacted by the new Tsar, Alexander III, in response to the continuing riots (which he initially blames on the Jews themselves). Although meant as temporary restrictions on Jewish movement and leasing of property within the Pale, these laws remain in effect until 1917.

1897

The first and only census conducted by the government of Russia which encompasses the entire Empire – Searchable on JewishGen.org

The census reflects a total of 4.9 million Jews living in the Pale of Settlement This accounts for 94% of the total Jewish population of the Russian Empire, and represents 11.6% of the Pale’s general population.

The late 1890’s herald the beginning of massive Jewish emigration from Russia to English-speaking countries…I hope this modest outline provides a basic understanding of the hostile environment which surrounded Jewish communities in pre-WWI Polish and Russian territories, which truly had a profound effect on all aspects of their lives. This knowledge can help us to narrow the scope of our searches and increase the chances of locating documents related to our Jewish ancestors. In applying historical context to our findings, we can more thoroughly interpret the significance of the information contained therein. Yes, sometimes learning the truth about our families is a painful experience, but the more we know about the world in which they lived, the better chance we have of piecing together our ancestors’ life stories and truly understanding who they were as individuals.Click here to receive help from an expert with your Jewish genealogy research.