By Rachel SilvermanSeven years ago, I embarked on the search for my great grandmother’s family history. I knew they were from a town in the Russian Pale of Settlement called Lanivtsy, which is within the borders of modern-day Ukraine. The family was Jewish and spoke the local dialects of Yiddish and Russian. They were mostly literate in Yiddish.

Sidebar: Yiddish is a combination of Hebrew, German, Russian, and several other languages, and is written using the Hebrew alphabet. Hebrew, like Arabic, has only a couple letters in its alphabet which English-speakers would categorize as vowels. Non-letter vowels, called diacritics, are represented by markings above or below the letters. In everyday writing, diacritics are generally omitted. If a word is unusual or unfamiliar, its pronunciation is open to the reader’s interpretation and linguistic knowledge.

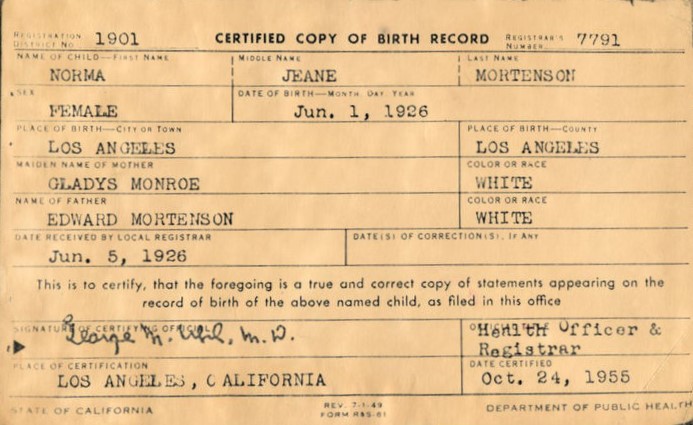

My great grandmother’s maiden name was Yoshpe (pronounced YOSH-peh). Not long into my search, I inherited a hand-drawn family tree, on which one of my long-dead relatives had spelled the family’s surname “Yoshpi.” This was a huge red flag. Sirens sounded in my ears. Right away, I knew that the family had probably never reached a group decision on how to spell their surname in English. My head reeled as I imagined the millions of possible letter combinations to sound out this one name...Transliterating--or spelling out--proper names which are originate in non-Roman alphabets is no easy task, whether you’re a Harvard Professor of Linguistics or a census taker with a high school diploma. When arriving in the United States, non-English speaking immigrants relied heavily on the language and spelling skills of those who recorded passenger arrivals -- most famously, at Ellis Island.While the efforts of arrivals recorders should not in any way be diminished, these records are the last place to impose limitations on your search. And census takers, wonderful as they are, aren’t always the best spellers, even when it comes to names. So what’s a genealogist to do when we face the ultimate name game?Enter the wildcard. A wildcard is a symbol that is used in place of one or more characters within text searches. You might recognize them as those funny symbols across the top of your keyboard (?, _, *, #). Get to know them, because in very short order, they will be some of your best genealogy research companions. But remember, wildcards can only be utilized in searches where the records have been indexed, that is, type- and handwritten records have been painstakingly typed out by some very patient soul, somewhere in the genealogy universe.In general, wildcard usage rules vary greatly from website to website - and some sites don’t allow for wildcards at all, such as EllisIsland.org. So, before typing in your search terms, be sure to look around for a wildcard key. Here are some examples of wildcard rules from several popular genealogy websites:Ancestry.com

* = zero or more characters

? = one single character

Either the first or last character must be a non-wildcard character

Names must contain at least three non-wildcard characters

FamilySearch.org

* = zero or more characters

? = one single character

Unlimited use of wildcards

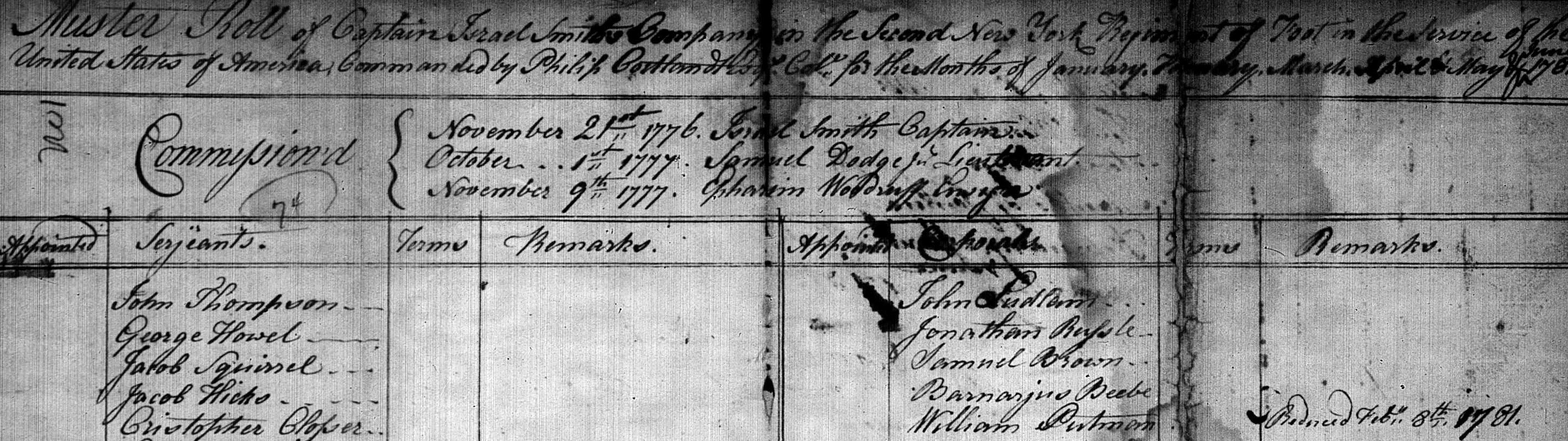

Fold3.com

* = zero or more characters

No option for single-character replacement

Only one wildcard may be used per search

Italiangen.org

* = multiple characters

_ = one single character

Unlimited use of wildcards

Utilizing my knowledge of wildcards and Hebrew language, I went to task on my great grandmother’s impossible family surname. Here are just a few of the combinations I used in my wildcard search:

y?shp?

y?sh?e

y?s?p*

y?s*p*

yos?p*

?os*pe

??s?pe

jos?p?

j?s?p*

While I got a lot of Josepher’s, I still got what I came for. Hits showed themselves in the forms of Yoshpe, Yoshpa, Yoszpe, Jospa, Joshpe, Joszpe, Joszpa, and even a couple mis-transcribed hits, Toshpe and Yashle. (I won’t even mention the thousands of records which I scrolled through in order to get the few results that actually applied to my family.)So you say your forebears were from Britain and spoke English, so there’s no need for you to bother with wildcards? Don’t leave your potential genealogy successes to chance! There are so many other variables that come into play, even when spoken language isn’t a barrier. Take the indexing process--mentioned above--where old records are typed and made searchable via computer. This process is largely based on a person’s ability to interpret someone else’s handwriting. Indexers are an invaluable part of the genealogy community, and they are tasked with typing out exactly what is written, even if it is possibly incorrect. Of course, sometimes handwriting is nearly impossible to make out, and indexers have to use their best judgment. Sadly, that leaves the records in question vulnerable to mis-transcription.And then there’s that pesky spelling issue. Immigration officials and census takers have proven time and again that names, no matter their cultural origin, can always be misspelled. For example, let’s look at the relatively common English surname “Randall.” Possible spellings include but are not limited to “Randal,” “Randle,” “Randel,” or “Randell” (all of which I have seen on hand-written documents).So what can we do to find a misspelled Randall? On Ancestry.com, which uses “*” to indicate zero or more missing characters, the search entry would read thusly: rand*l* For those of you who use Ancestry.com often, I would not use “?” here, because it indicates an absolute, single missing character, which might eliminate positive results from our search. “*” takes into account the possibility that there may not be any characters at all between “d” and “l”. Yes, using “*” will give us a ton more search results than “?”--most of which will not apply to our research--but it will also help us to avoid inadvertently eliminating the results we actually want. Remember, in genealogy, the more records you have to sift through, the more likely you are to find something that applies to your personal quest. In essence, more is more, and using wildcards will get you just that. And no matter your family’s geographic, linguistic, or cultural history, wildcards are an important part of your research toolbox. So play by the rules, get creative, and don’t give up!