The years following the Civil War—from 1865 to 1877—marked the Reconstruction Era, a time of monumental change, uncertainty, and rebuilding in the United States. For genealogists, this era offers an essential opportunity to document family transitions: from slavery to freedom, from war to settlement, and from fractured records to new legal identities.

At Trace, we help clients uncover ancestors’ lives and legacies during this pivotal period in American history.

The Reconstruction Era refers to the period from 1865 to 1877, following the end of the American Civil War. It was a time of profound transformation, as the nation grappled with reintegrating the Southern states and determining the status of nearly four million newly freed African Americans. While the war had ended slavery, the challenge of defining freedom in practice, politically, socially, and economically, had just begun.

During Reconstruction, the federal government enacted sweeping legislation aimed at rebuilding the South and securing civil rights for formerly enslaved people. The 13th Amendment formally abolished slavery in 1865. This was followed by the 14th Amendment in 1868, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to anyone born in the United States, and the 15th Amendment in 1870, which extended voting rights to Black men. These legal advances laid the foundation for modern civil rights, but they were fiercely contested from the start.

To support the transition from slavery to freedom, the government established the Freedmen’s Bureau, which operated from 1865 to 1872. The Bureau provided food, housing, medical aid, and legal support, and helped establish schools and churches for African Americans. It also helped reunite families separated by slavery and war, leaving behind a remarkable record trail for genealogists.

At the same time, formerly enslaved people began building independent communities, forming churches and schools, purchasing land, and even holding public office. For a brief time, Reconstruction saw the highest number of Black elected officials in U.S. history until the late 20th century. However, the period was also marked by violent backlash from white supremacist groups, voter suppression, and contested federal oversight.

By 1877, Reconstruction formally ended when federal troops withdrew from the South as part of the Compromise of 1877. What followed was the rise of Jim Crow laws, segregation, and widespread disenfranchisement, but the records created during Reconstruction continue to serve as a vital resource for understanding family histories during a period of transition and redefinition.

For genealogists, the Reconstruction Era represents both a turning point and a rare window into the lives of those who were previously undocumented or hidden in the historical record.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, officially known as the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, was established by the United States Congress in March 1865 to assist formerly enslaved people and impoverished Southern residents in the wake of the Civil War. Active until 1872, the Bureau became one of the most far-reaching efforts by the federal government to rebuild the South and offer direct aid to individuals, especially African Americans, transitioning from slavery to citizenship.

From a genealogical perspective, the Freedmen’s Bureau generated some of the most important records available for tracing African American families during the Reconstruction era. These documents often represent the first time formerly enslaved individuals were recorded by full name in government records. The Bureau’s work included overseeing labor contracts between freedmen and employers, administering rations and healthcare, resolving legal disputes, building schools, and formalizing marriages that had previously been considered illegitimate under slavery.

Among the most valuable genealogical resources are labor contracts, which often list entire families by name, along with former enslavers and employers. Marriage records created by the Bureau helped legalize unions among couples who had long lived together but had never been allowed to marry under the law. Educational records from Freedmen’s schools also survive, documenting early Black students and teachers across the South. Additionally, legal correspondence and case files offer rare insight into the daily lives and struggles of newly freed people, from wage disputes to reuniting families separated by war and slavery.

Freedmen’s Bureau records are especially useful because they document the activities of African Americans during a period when state and local governments often failed to include them in official records. The Bureau operated offices in nearly every former Confederate state, meaning that whether your ancestors lived in Mississippi, Virginia, or Louisiana, there is a strong chance they interacted with or were recorded by the Bureau in some form.

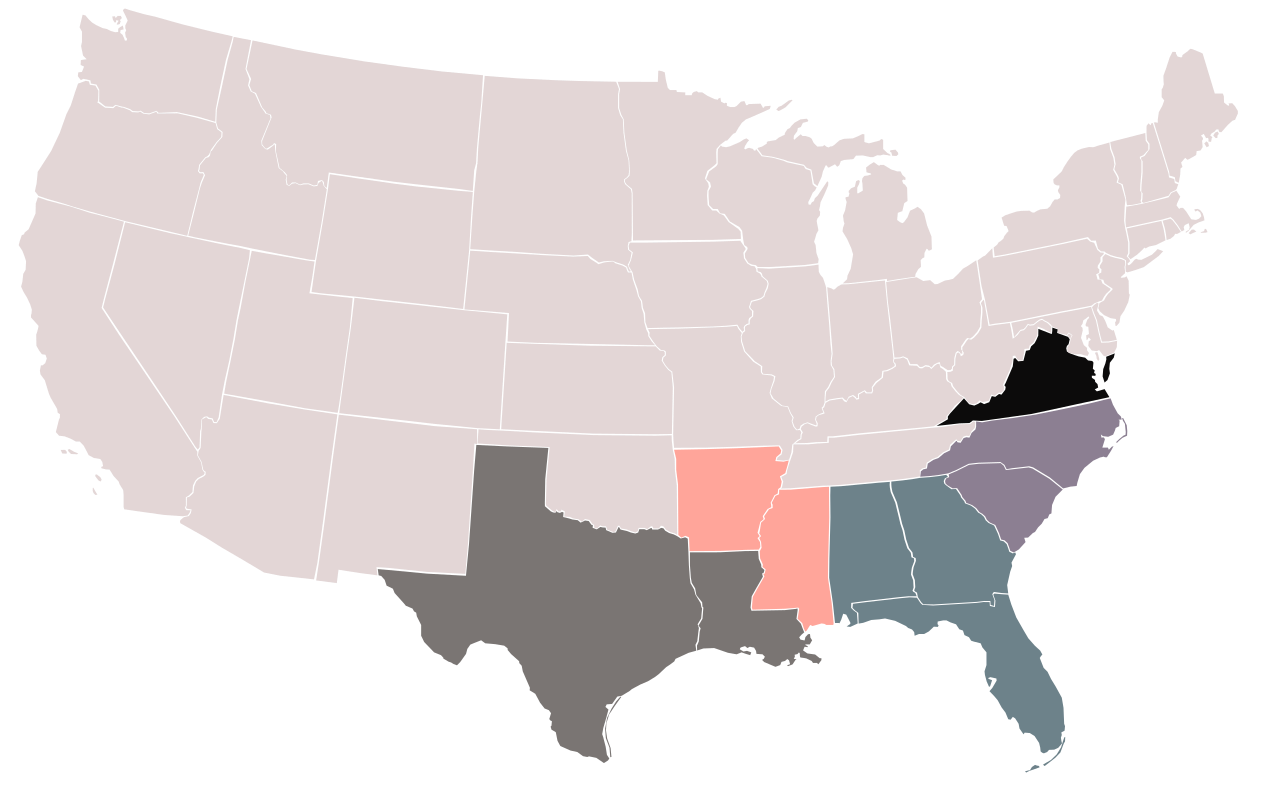

Following the Civil War, a faction of Congress viewed President Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction policies as overly lenient toward former Confederates. In response, the Military Reconstruction Acts of March 1867 divided ten former Confederate states (excluding Tennessee) into five military districts. Each district was administered by Union Army generals who were to maintain order, remove former Confederate officials from power, register black and white voters, and oversee conventions that would draft new state constitutions.

The districts were structured as follows: the First encompassed Virginia; the Second included North and South Carolina; the Third oversaw Georgia, Alabama, and Florida; the Fourth covered Arkansas and Mississippi; and the Fifth supervised Texas and Louisiana. Union generals like John Schofield, Daniel Sickles, John Pope, Edward Ord, and Philip Sheridan held authority as military governors, charged with enforcing federal policies on civil rights, suffrage, and governance. Their presence enabled the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, empowered African Americans to participate in elections, and paved the way for Black representation in Southern legislatures.

For genealogists, military district records serve as a crucial forensic lens. These collections often contain voter registration rolls, details of newly enfranchised citizens, court proceedings, petitions, and military orders detailing local governance. Many formerly enslaved individuals make their first appearance in official records during this time, such as voter rolls or petitions for restored land or rights. Mapping ancestors’ residency during this period can uncover newly digitized sources that bridge gaps between fragmented Civil War-era documents and later federal records.

Even if your ancestors weren’t politically active or directly impacted by war, Reconstruction-era records can bridge crucial gaps in family history, especially for:

This period is especially valuable for researchers looking to trace individuals who are difficult to locate in pre-1870 records, including those newly listed by full name in the 1870 Federal Census.

We specialize in identifying and interpreting records from this complex period. Our services include:

Each project is tailored to your specific lineage, geography, and research goal.

The following record sets are especially valuable for research between 1865 and 1877:

We also access rare sources from historical societies, church archives, and southern state libraries.

Our Reconstruction-era research may reveal:

If you’ve struggled to locate family members before 1870, or want to understand how the Civil War and Reconstruction impacted your lineage, we’re here to help.

📬 Contact Us to start a customized genealogy project focused on the Reconstruction era. Our research brings together public records, private collections, and historical insight to tell your family's story.

What if I don’t know whether my ancestors were formerly enslaved?

We can assess property records, census data, and local histories to determine likely statuses and connections.

Are Freedmen’s Bureau records online?

Some are digitized, but many are not fully indexed. We conduct in-depth searches using both online and archival sources.