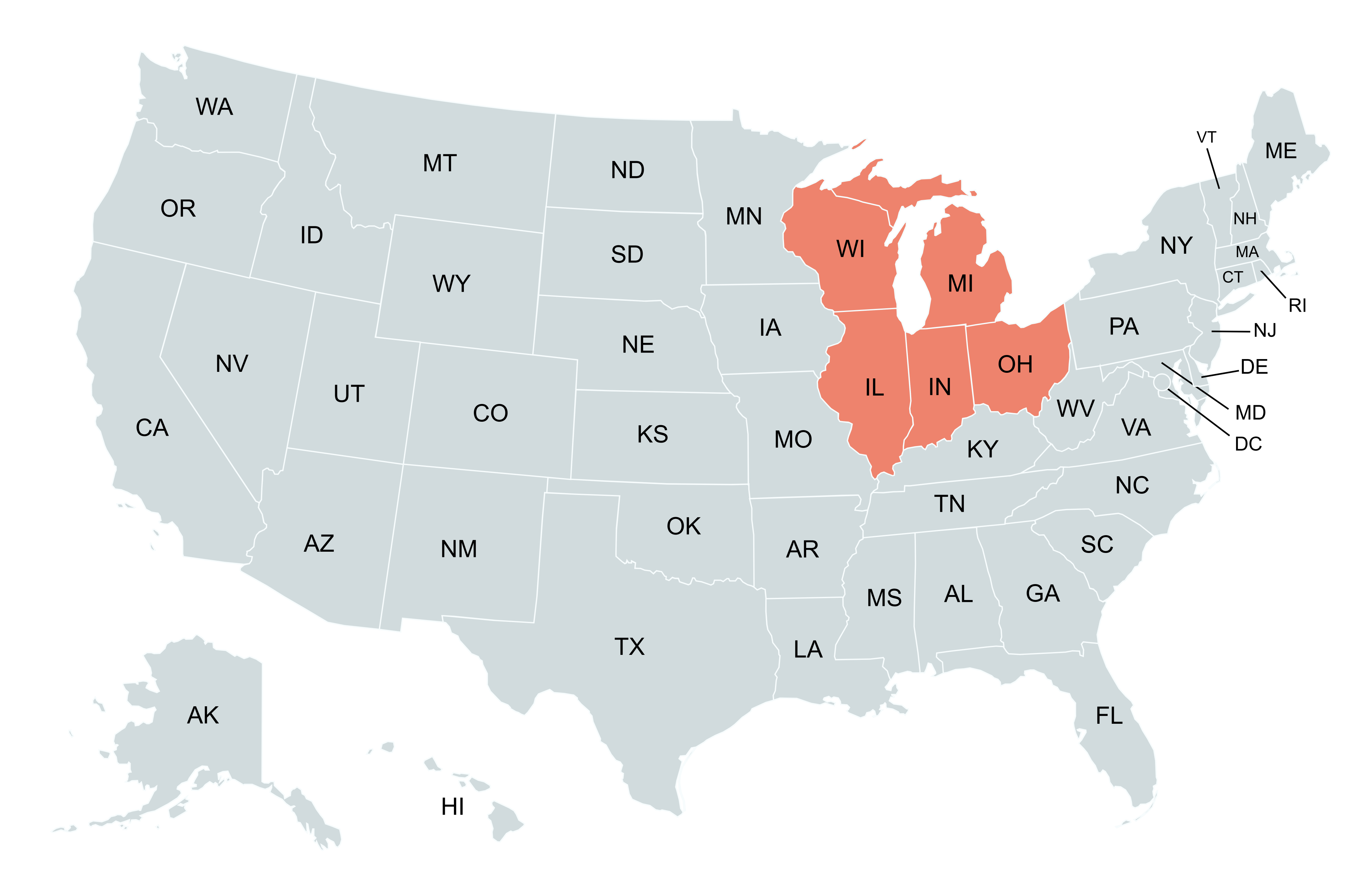

The American Midwest, comprised of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, and also known as the Great Lakes Region, is a cornerstone of genealogical discovery for countless families. From early pioneer settlements to industrial boomtowns, these states offer a dynamic blend of historical movements, diverse cultural migrations, and well-preserved records that make them prime territory for uncovering your family history.

Whether you're just beginning your genealogical journey or expanding a well-documented tree, the Midwest's unique blend of urban archives, rural courthouse records, and ethnic community histories creates a rich foundation for building your ancestry.

Historically, the Midwest has served as a dynamic crossroads for migration, innovation, and community building, a region where the story of America’s growth is deeply etched into its landscape. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, settlers from New England and the mid-Atlantic ventured westward into newly formed territories like Ohio and Indiana, many of them Revolutionary War veterans receiving land grants or pioneers seeking fertile farmland. This wave of migration intensified following the Northwest Ordinance, laying the groundwork for rapid population growth, township formation, and agricultural development.

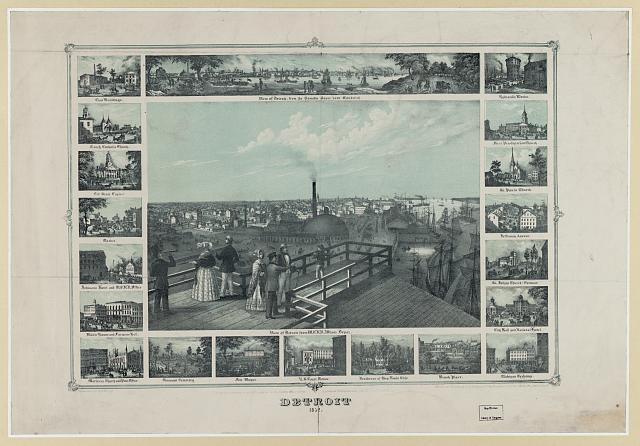

As the 19th century progressed, the construction of the Erie Canal, the expansion of railroads, and the rise of Great Lakes shipping routes brought transformative economic opportunities and ushered in massive immigration. Millions of newcomers from Germany, Ireland, Poland, Italy, Norway, Sweden, and Eastern Europe made their way to the Midwest, many settling in burgeoning industrial cities like Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and Milwaukee. These cities became economic powerhouses, drawing workers into steel mills, meatpacking plants, automobile factories, and shipyards, while the surrounding rural communities continued to attract farming families.

In the early to mid-20th century, the region witnessed another pivotal movement during the Great Migration, as hundreds of thousands of African American families from the South moved north in search of jobs and better living conditions. Their arrival profoundly shaped the cultural and economic fabric of cities across Illinois, Ohio, and beyond. The Midwest also played critical roles in the Underground Railroad, Civil War recruitment, and other defining national moments, leaving behind records that continue to tell those stories today.

From homesteads and harbors to factories and freedom trails, every movement—every arrival, settlement, and departure—left a paper trail. These trails are now the building blocks of genealogical research. Whether your ancestors were early pioneers, recent immigrants, or part of transformative social movements, the genealogy of the Midwest is a reflection of the American experience: a continuous wave of settlement, resilience, and reinvention. From rural farming communities to bustling urban neighborhoods, each Midwestern state offers a powerful lens into your family’s past.

To build a thorough family history in the Midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, researchers rely on a wide variety of genealogical sources—many of which are remarkably well-preserved across the region. Most counties and state governments began recording births, marriages, and deaths in the mid- to late 1800s, although some church parishes and local communities kept vital records even earlier.

Federal and state census records, available from 1790 through 1950, are essential for tracing family households at ten-year intervals. These records offer valuable details on occupations, birthplaces, property ownership, and household structures. Other indispensable resources include land and property deeds, which reveal patterns of settlement, family migration, and estate divisions, as well as probate and court records, such as wills, guardianship documents, and estate inventories that can uncover lesser-known family relationships.

Church and religious registers often predate official state records and include baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burial information—especially important in areas with strong Catholic, Lutheran, or Quaker communities.

Military service files, from Civil War muster rolls to World War draft cards, provide insight into your ancestors' patriotic service and personal details like age, occupation, and physical description. For those with immigrant ancestors, naturalization and immigration documents, including port arrival records, border crossings, and petitions for citizenship, often contain rich personal narratives.

Local newspapers and obituaries are another genealogical goldmine, offering announcements, marriage notices, advertisements, and community events that bring ancestors to life in a way that official documents often cannot. In many towns, city directories supplement census gaps and help track families between federal enumerations.

One of the Midwest’s greatest genealogical assets lies in the preservation of county-level archives. Despite occasional losses due to fire or deterioration, many counties, particularly in rural areas, have maintained remarkably complete and well-organized collections of documents dating back over a century. These records are increasingly available through digitized online repositories, as well as local courthouses, historical societies, and genealogy centers, making the region both accessible and rewarding for family historians.

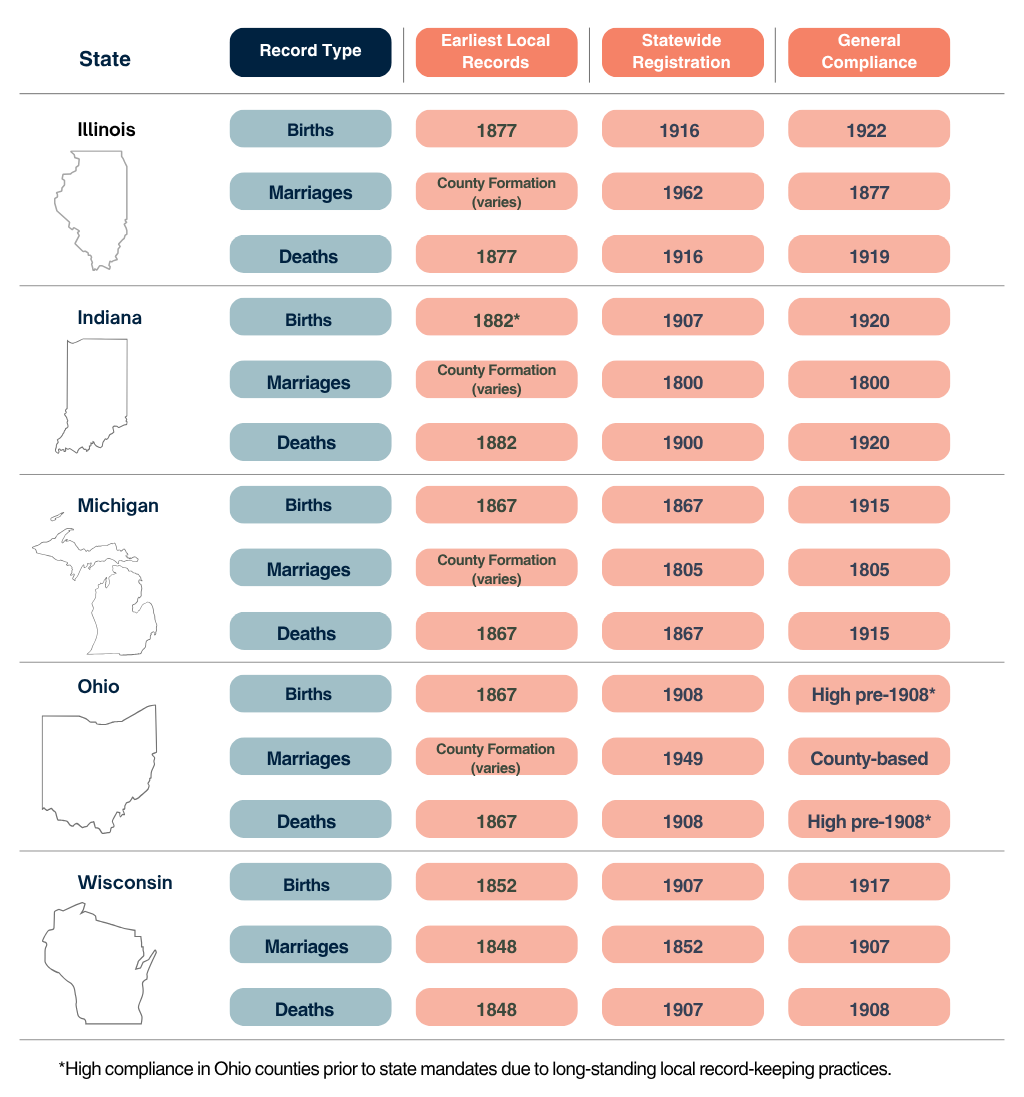

Understanding the start dates of vital records—births, marriages, and deaths—is essential for genealogists researching in the Midwestern states. Each state began formal civil registration at different times, and the level of compliance often varied depending on the county and the type of record.

In Illinois, counties began keeping some birth and death records around 1877, though coverage was spotty. Statewide registration of these events did not begin until 1916, and general compliance followed by the early 1920s. Marriage records were kept at the county level from formation, but weren’t routinely forwarded to the state until 1962.

Indiana has one of the earliest marriage registration histories in the Midwest, with records dating to 1800. However, official state-level birth and death registration began later in 1907 and 1900, respectively, with general compliance not reached until 1920. Some cities began local registration of vital events as early as 1882.

In Michigan, vital recordkeeping is relatively early and centralized. Statewide recording of births, marriages, and deaths began in 1867, though widespread compliance with birth and death registration was not achieved until 1915. Marriages were well-documented from the early 1800s.

Ohio began recording births and deaths at the county level in 1867, with statewide registration becoming standardized in 1908. Although formal statewide marriage registration did not begin until 1949, marriage records had long been maintained by county probate courts, and compliance was generally high even before centralization.

Wisconsin has some of the earliest birth and death records in the Midwest, with local documentation beginning in 1852 and 1848, respectively. Statewide registration was implemented in 1907, with general compliance for deaths achieved by 1908 and for births by 1917. Due to varying practices across counties, there is no clear general compliance date for marriages.

Each record type—whether a birth certificate from a remote farming town or a death register from an industrial city—offers clues that help piece together multigenerational family stories. The region's robust recordkeeping infrastructure, especially at the county level, makes the Midwest an invaluable area for building comprehensive family histories.

In Illinois, both urban and rural genealogical records flourish. Chicago alone was a major destination for immigrants and a key site for internal migration. Researchers can access civil registration records starting in 1916, but earlier data is often found through churches and cemeteries. Downstate Illinois is rich in pioneer-era records, especially along the Mississippi River and in the counties that once bordered Native American territory.

Indiana presents a particularly strong case for early American genealogists. As a transitional state between the eastern colonies and the far west, it attracted settlers as early as the 1810s. Its courthouse archives often contain early land patents, Quaker meeting minutes, Methodist circuit rider records, and Civil War enlistment papers. Indiana’s rural records are a model of organization and breadth.

Michigan, bordered by four of the Great Lakes, became a gateway to both industry and agriculture. From the French traders of the Upper Peninsula to the auto workers of Detroit, the state’s population has always been diverse. Catholic and Lutheran churches in cities and towns hold generations’ worth of vital data. Immigration records from Canadian border crossings are especially rich, making Michigan a prime target for those with French Canadian or Scandinavian heritage.Ohio holds one of the most diverse arrays of genealogical sources in the country. As the first state admitted from the Northwest Territory, it has detailed census rolls, early tax lists, bounty land grants, and a deep network of church and cemetery records. German ancestry dominates many counties, while early abolitionist movements and Underground Railroad activity leave behind powerful historical footprints.

Wisconsin rounds out the Midwestern quintet with a heavy emphasis on farming communities, strong immigrant clusters, and well-documented civic records. With large populations of Germans, Norwegians, and Poles, Wisconsin’s religious and naturalization records offer insights into old-country origins and local assimilation. In addition to state-level archives, many counties maintain family bibles, township plat maps, and community-written histories that are invaluable for genealogists.

While statewide registration systems form the backbone of genealogical research in the Midwest, the region’s major cities maintained their own local registration offices and civic archives, often generating detailed and earlier records than their rural counterparts. Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Indianapolis not only attracted enormous populations during the 19th and 20th centuries, but also developed robust municipal systems that captured the lives of immigrants, migrants, and working-class families with remarkable detail.

In Chicago, Illinois’ largest city and one of the busiest immigration hubs in the U.S., local government began recording births and deaths in 1871, shortly after the Great Chicago Fire. Though Illinois did not mandate statewide registration until 1916, Chicago maintained its own civil registration system under the jurisdiction of the Cook County Clerk’s Office and Chicago Department of Public Health. The city also maintained separate marriage registers, naturalization indexes, and coroner's inquest records, many of which survive today through microfilm and digital repositories. Given its vast immigrant population, including Germans, Irish, Italians, Poles, Jews, and African Americans arriving during the Great Migration, Chicago is also home to a rich network of ethnic parish registers, labor union documents, and community newspapers, offering critical insights beyond standard civil documentation.

Detroit, Michigan’s industrial powerhouse, began recording births and deaths through Wayne County in the mid-1860s, a few years before Michigan’s 1867 statewide registration law. However, compliance was spotty in outlying areas, making Detroit’s city records especially important for early documentation. The City of Detroit Health Department and Wayne County Clerk maintained detailed registers, especially as the city’s population surged in the early 20th century with the rise of the automobile industry. Detroit also holds extensive records on the Great Migration, during which thousands of African American families from the South settled in the city. Researchers can explore church registers, fraternal organization records, Black-owned funeral home logs, and city directories that track neighborhood patterns and housing changes across decades.

In Cleveland, Ohio, the Cuyahoga County Archives preserve one of the state's most complete sets of county and municipal records, including birth and death registers from 1867, years before the 1908 state requirement. Cleveland’s early city directories and immigrant aid society records are especially helpful for locating Eastern European and Jewish families, who arrived in large numbers in the late 1800s. The city’s Catholic diocesan archives, along with Lutheran, Baptist, and Orthodox registers, capture a wide variety of ethnic congregations. Cleveland was also deeply involved in the labor and suffrage movements, and researchers may find relevant material in union records, women’s clubs, and settlement house files.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin’s largest city, has long maintained independent records of vital events, particularly for its heavily German and Polish immigrant populations. Although Wisconsin implemented statewide registration in 1907, Milwaukee's vital records began locally in the mid-to-late 1800s, often maintained by the Milwaukee Health Department and city registrar’s office. The city’s many Catholic parishes, along with Lutheran synods and ethnic newspapers, preserved baptisms, marriages, and burial notices that predate official state filings. Milwaukee is especially rich in German-language documents, which may require translation but often provide in-depth biographical information, including hometowns in Europe, immigration dates, and extended kinship ties.

In Indianapolis, Indiana’s capital and a growing industrial city by the mid-19th century, the Marion County Health Department began tracking births and deaths before the state’s 1907 mandate. Local recordkeeping, including school registers, real estate transactions, and tax lists, can help fill in gaps in census and civil documentation. The city is also home to several repositories like the Indiana State Library, Indiana Historical Society, and African American Genealogy Group of Indiana that specialize in regional migration histories, freedmen’s records, and early settler documentation. Indianapolis was an important node in the Underground Railroad, and surviving court records, church minutes, and abolitionist publications may hold unexpected treasures for descendants of freedom seekers.

Together, these urban centers offer genealogists a powerful supplement to state-level repositories. Their early registration systems, denominational diversity, and immigrant community networks produced layers of records rich in address data, parental origins, occupational history, and religious affiliations. Whether you’re tracing ancestors through a steelworker's death certificate in Cleveland or locating a German baptism in Milwaukee, these city archives often contain the key to family stories that broader indexes may overlook.

The Midwest doesn’t just represent a region, it represents a people’s movement. From newly arrived immigrants seeking a better life, to early pioneers claiming land, to factory workers forging steel and automobiles, the families who lived here shaped the country’s culture, economy, and progress.

Exploring your family's roots in the Midwest is more than a search for names and dates, it's a discovery of resilience, transformation, and legacy. The archival richness of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin allows researchers to paint full, vivid portraits of those who came before. Whether you uncover land deeds that date back to the 1830s or read a century-old obituary from a local newspaper, each record brings you closer to understanding your family’s journey.

Unraveling your family history in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, or Wisconsin can uncover not only names and dates, but powerful stories of resilience, migration, and legacy.

Contact us today to get started!

Explore now and let the Midwest reveal your past—one ancestor at a time.

Continue exploring the full range of our genealogical expertise by diving into these additional regions and services: