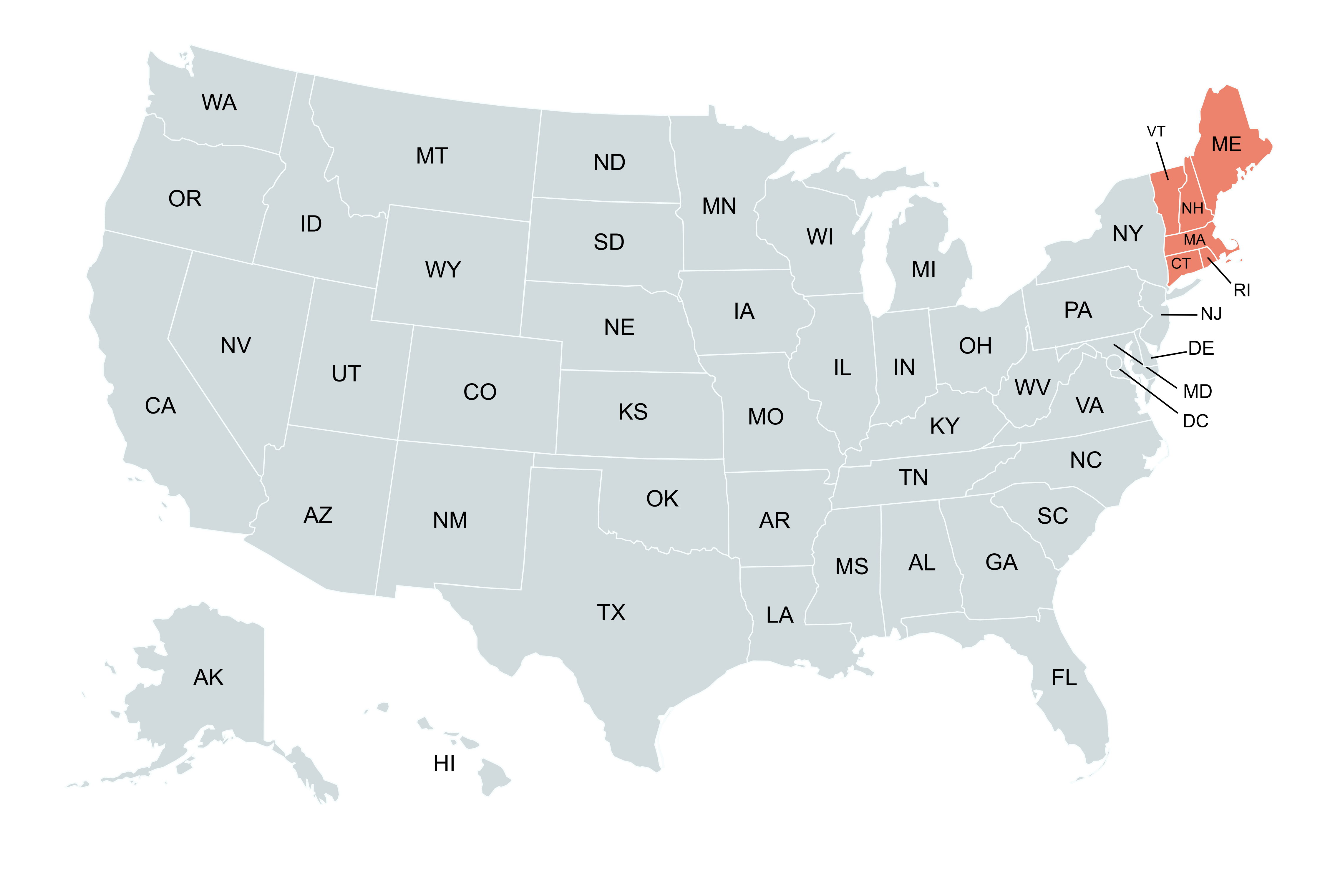

New England, comprising the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont, is one of the most historically significant and genealogically rich regions in the United States. As the site of some of the earliest permanent European communities, New England has maintained a deep tradition of local recordkeeping that stretches back to the 1600s. These long-standing town and church archives make it an unparalleled region for tracing early American ancestry.

Whether your forebears were Puritans establishing towns in colonial Massachusetts, French Canadians settling in northern Maine, or 19th-century immigrants working in New England’s bustling textile mills, this region offers generations of preserved records and stories waiting to be rediscovered.

New England’s genealogical richness is deeply rooted in its singular place in American history. Across the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont, the story of the United States began—not just in battles and declarations, but in town halls, meetinghouses, and homesteads. The region’s legacy of religious experiment, revolutionary fervor, civic order, and westward movement created a recordkeeping tradition that is both remarkably early and uniquely enduring.

The colonial foundations of New England were built by settlers who sought to create new societies based on spiritual conviction and communal governance. In the 1620s and 1630s, the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies emerged as Puritan strongholds where religious conformity and literacy were prized. From these early settlements, an infrastructure of recordkeeping quickly evolved. Town clerks tracked births, deaths, marriages, land transfers, and tax payments; churches recorded baptisms, memberships, and excommunications. This pattern of detailed local documentation—anchored in both civic and ecclesiastical life—became a defining feature of the region.

While Massachusetts was a model of centralized Puritan order, Rhode Island was founded in deliberate defiance of it. Established by religious dissenters like Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, Rhode Island became a haven for Baptists, Quakers, Jews, and others who faced persecution elsewhere. Its embrace of pluralism fostered a decentralized recordkeeping culture, where genealogical clues are often found in church archives, family papers, or community-led registries rather than state repositories.

Connecticut and New Hampshire followed similar paths rooted in Puritan settlement but increasingly diverse as new towns were chartered and colonial control shifted. Connecticut’s town records are particularly robust, capturing everything from livestock branding to schoolteacher contracts. In New Hampshire, seacoast towns like Portsmouth developed early and left behind records reflecting maritime commerce, land speculation, and transatlantic migration.

Vermont tells a different story. It was never formally one of the original colonies, but rather declared itself an independent republic in 1777, remaining autonomous until it joined the Union in 1791. Its early records reflect this maverick spirit: militia lists, land grants, and tax rolls paint a picture of a frontier society deeply connected to the revolutionary cause and westward expansion. Many Vermont settlers hailed from Massachusetts and Connecticut, linking the Green Mountain State genealogically to families across southern New England.

Maine, too, has a hybrid history. As part of Massachusetts until 1820, its early records are interwoven with those of its parent colony. Fishing villages, lumber camps, and shipbuilding ports across coastal Maine were settled by both English colonists and French Canadians. In the north, Franco-American communities grew around Catholic parishes that became crucial recordkeepers for families migrating from Quebec.

The colonial era gave way to revolution, and New England again played a pivotal role. From the Boston Tea Party to the Lexington and Concord skirmishes, New England towns mobilized for independence. Local records document enlistments, supply votes, and payments to soldiers—rich sources for identifying Revolutionary War ancestors. Patriot activity was mirrored by deep divides within communities, and these tensions often show up in court cases, estate disputes, and militia reorganizations.

In the 19th century, New England transformed once again, this time into the engine of America’s industrial and social revolutions. Textile mills in Lowell, Manchester, and Pawtucket fueled economic growth and drew immigrants from Ireland, Italy, French Canada, and Eastern Europe. These new populations added layers of Catholic, Orthodox, and Jewish recordkeeping traditions to an already complex archival landscape. Cities began collecting health data, issuing burial permits, and expanding school systems, creating further genealogical trails.

Simultaneously, thousands of New Englanders, especially younger sons and daughters, joined the westward migration, settling in New York, Ohio, Michigan, and beyond. They often left behind departure notices, land sales, and family correspondence, linking east and west through generational ties. Others stayed, leaving footprints in abolitionist societies, women’s clubs, temperance organizations, and educational institutions like Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth.

Genealogists benefit today from this historical continuity and civic consciousness. Few regions in the world maintained such a consistent commitment to public recordkeeping, religious preservation, and democratic accountability. Whether tracing ancestors who arrived in the 1630s or the 1930s, researchers in New England will find that every layer of the region’s history, its theology, its politics, its frontier spirit, has been documented, indexed, and often carefully preserved.

New England genealogy is defined by the depth and continuity of its historical recordkeeping. Thanks to its long tradition of literacy and community governance, nearly every town kept detailed civil and ecclesiastical records dating back to its founding.

Vital records, including births, marriages, and deaths, were maintained at the town level in most New England states from the 1600s onward. These records often include details such as parents’ names, occupations, and causes of death, long before other regions adopted similar practices. Massachusetts, for example, has printed volumes of town vital records extending back to 1635.

Church registers, particularly those from Congregational, Baptist, Quaker, and Universalist denominations, offer baptism, marriage, and burial data that predate or supplement town records. These are especially important in Rhode Island, where religious diversity led to decentralized recordkeeping.Researchers will also find extensive land deeds, probate files, town meeting minutes, and military rosters, including colonial militias and Revolutionary War service. Census records, available from 1790 forward, are complemented by state census schedules, tax lists, and voter rolls, many of which are digitized or published in town histories.

The region's early institutions such as Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, and Brown generated alumni directories, church affiliation logs, and ministerial records that are useful for tracing elite and educated family lines. Immigration records through Boston Harbor, and later Ellis Island, also reflect the waves of 19th- and early 20th-century newcomers who settled in New England cities.

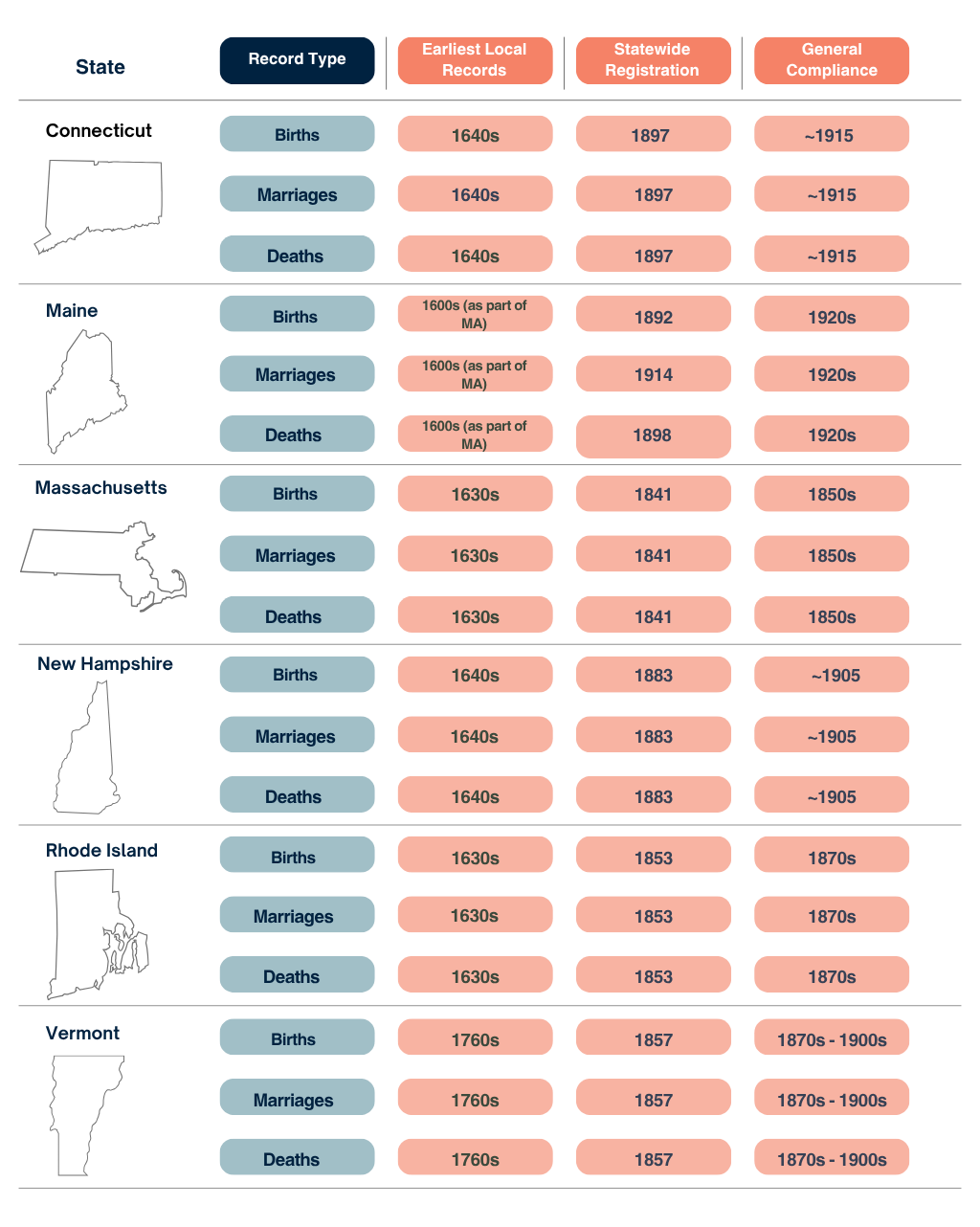

Unlike other U.S. regions that relied heavily on county-level systems, New England’s genealogical framework is rooted in town governance. Understanding when each state began civil registration can guide researchers toward the most productive sources.

Most New England states began maintaining town vital records in the 1600s or early 1700s. However, formal statewide registration systems were implemented later. Massachusetts and Vermont led the way with 19th-century legislation, while Maine, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire centralized recordkeeping in the early 20th century. Despite this, earlier town records remain the most detailed and widely used sources.

Because compliance varied, researchers should always check town clerks’ offices, state archives, and local historical societies. Many of these institutions also house records for cemeteries, school districts, and selectmen’s reports, which provide further genealogical insights.

Each New England state offers a distinctive path through American history. From seafaring towns to abolitionist strongholds, here’s what makes each state a vital part of your family’s past.

Connecticut combines deeply rooted Puritan settlements with industrial growth and immigration. Town records are exceptionally strong, and the Connecticut State Library and local town halls preserve land, probate, and church registers going back to the 17th century.

Maine, once part of Massachusetts, shares many of its early colonial records. French Canadian immigration into northern Maine is well documented through Catholic parish records, border crossings, and bilingual registers. Fishing towns, shipyards, and lumber camps all produced rich labor and community records.

Massachusetts is arguably the most thoroughly documented state for early American genealogy. Its towns were among the first to register births, marriages, and deaths, and many have published printed town records. Boston played a key role in every major wave of immigration and reform, with strong archives for Irish, Italian, and Jewish communities. The state’s many historical societies and educational institutions further enhance access to personal and institutional histories.

New Hampshire offers strong Revolutionary War, land, and tax records, especially in early settlements and seacoast towns. Migration patterns show New Hampshire-born families moving westward, often leaving behind probate files and land transfers. Concord and Portsmouth feature prominently in early trade and civic development, while inland towns maintained robust church and town documentation.

Rhode Island stands apart with its tradition of religious tolerance and independent spirit. Home to Baptists, Quakers, and other dissenting groups, it maintained unique religious and civic records. Early vital records are often stored at the town level and supplemented by family bible collections and genealogical societies, while the Rhode Island State Archives preserves colonial land deeds, vital records, and naturalization data.

Vermont, a latecomer to statehood in 1791, holds strong records tied to its independence movement and early settlers. Town clerks are the primary custodians of vital and land records, while military rosters, tax assessments, and settlement maps reflect the state’s revolutionary roots and frontier identity. Vermont’s close genealogical ties to Massachusetts and Connecticut make it an essential stop for tracing regional migrations.

While state archives and centralized collections are invaluable, many of New England’s richest genealogical records remain at the town and municipal level. This region’s tradition of local governance—through town meetings, elected clerks, and parish-based recordkeeping—means that vital clues about your ancestors’ lives may be found only in community-specific repositories.

Town offices often preserve records that go well beyond births, marriages, and deaths. Researchers may encounter school attendance logs, teacher appointment lists, militia enrollment books, selectmen’s reports, property tax rolls, pauper support accounts, burial permits, and town poor ledgers. In some cases, these documents extend back to the 1700s and are still stored on-site at the town clerk’s office, requiring in-person requests or correspondence with local staff.

In larger cities, local governments and religious institutions created independent civil and ecclesiastical records that predate or operate separately from state-mandated systems. For example, in Boston, Providence, Hartford, and Portland, boards of health began tracking births and deaths decades before statewide registration. These records often contain additional data such as street addresses, occupations, and parental birthplaces—details that were not always recorded in later, standardized forms.

Religious diversity adds another layer to New England’s archival richness. Catholic diocesan archives in cities like Boston, Burlington, and Manchester preserve sacramental registers—including baptisms, marriages, and confirmations—from large immigrant parishes that served Irish, French Canadian, Italian, Polish, and Portuguese communities. Jewish congregations kept meticulous circumcision, yahrzeit (death anniversary), and burial records, often tied to specific synagogues and chevra kadisha (burial societies). Lutheran, Episcopal, and Orthodox Christian communities also maintained robust records of membership, services, and interments, reflecting the region’s expanding ethnic and religious complexity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Beyond town halls and churches, researchers should turn to New England’s outstanding library and historical society networks, many of which curate genealogical collections of regional and national significance. The Boston Public Library houses a premier collection of city directories, historical newspapers, and voter registrations. The Maine Historical Society in Portland offers manuscript collections, family papers, and maritime records documenting coastal life and French Canadian immigration. The Rhode Island State Archives holds naturalization records, colonial land transactions, and unique marriage intentions. The New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS), headquartered in Boston, provides access to digitized town records, compiled genealogies, and scholarly databases that span all six New England states.

In smaller towns, local historical societies, genealogical groups, and even village libraries often maintain vertical files, transcriptions of old cemeteries, unpublished family histories, and oral history interviews. These local sources are frequently overlooked but can yield personal details and family relationships not found anywhere else.

In short, New England’s city and town archives are not just supplemental—they are foundational. Anyone building a comprehensive family history in the region should combine statewide collections with a close examination of the local records created and preserved by the communities where ancestors lived, worshipped, and worked.

New England’s value for genealogists lies not just in how early records begin, but in how carefully they were kept. Generations of town clerks, ministers, teachers, and family historians contributed to a paper trail that is unusually rich, consistent, and accessible.

Whether you’re seeking Revolutionary War pension files, a 1680 baptism in Salem, or a 1920 French Canadian marriage in Lewiston, New England offers a unique blend of historical depth and genealogical possibility. Few regions offer such a continuous record of family life across four centuries.

Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont each have their own legacy—but together they form a cradle of American identity. With extensive town records, early church registers, and immigrant-era documentation, this region is a dream for genealogists.

Contact us to start tracing your New England roots today—and bring your family's early American story into focus, one record at a time.

Ready to go further? Let us help you explore these additional genealogical specialties and geographic focuses.