The South Central region, comprised of Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas, offers an extraordinary genealogical landscape shaped by early frontier expansion, European colonization, Civil War upheaval, and the fusion of Indigenous, Hispanic, African, and Anglo-American traditions. With records that span Spanish missions, territorial governments, plantation economies, and cattle ranching empires, this region is a powerhouse of genealogical depth and diversity.

From colonial Louisiana to homesteaders on the plains, the South Central states are a vital destination for researchers seeking rich documentation of American settlement, migration, and identity.

Genealogical research in the South Central region is deeply intertwined with centuries of shifting borders, cultural exchanges, and evolving systems of governance. Long before these territories joined the United States, they were home to powerful Indigenous nations and claimed at various times by colonial empires including Spain, France, and Mexico. These overlapping sovereignties have left behind a remarkable mosaic of records—some in Spanish, some in French, and many in multiple languages—each offering a unique window into the lives of early inhabitants.

Louisiana and Texas stand out for their complex colonial pasts. Louisiana was governed by France, then Spain, then France again before its 1803 acquisition in the Louisiana Purchase. Parish registers, notarial deeds, and colonial censuses date back to the early 1700s and often include free people of color, enslaved individuals, and mixed-race families. Texas, meanwhile, shifted from Spanish control to the short-lived Mexican Republic, then to its own independence as the Republic of Texas before statehood in 1845. Researchers exploring early Texas ancestors will encounter Spanish land grants, Catholic mission records, and Republic-era headright certificates that trace settlement into the interior.

Further north, Missouri and Arkansas became key destinations during the westward expansion of the early 1800s. Following the Louisiana Purchase, American settlers began arriving via river routes and the overland trails. Missouri’s statehood in 1821 and Arkansas’s in 1836 brought new administrative systems and recordkeeping standards, but territorial records from prior decades—including land patents, tax lists, and early court cases—remain essential for genealogists. These two states also saw large waves of German immigrants, creating rich Lutheran and Catholic church archives.

Kansas and Oklahoma carry a different but equally significant historical weight. Kansas was a battleground in the national debate over slavery, earning the moniker “Bleeding Kansas” for the violent clashes that accompanied its transition from territory to free state. Records from this era include abolitionist tracts, military muster rolls, voter petitions, and early homesteader claims under the 1862 Homestead Act. Kansas became a hub for both African American migration, most notably the Exoduster movement, and immigrant farming communities from Europe.

Oklahoma, once designated as Indian Territory, became a center of Native American displacement and resilience. Tribal removal policies like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 brought the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole nations to the region. The resulting records, Dawes Rolls, land allotment records, and Bureau of Indian Affairs correspondence, are among the most genealogically detailed tribal documents in the country. Later, Oklahoma became a destination for settlers from neighboring states, especially after the 1889 Land Run, further diversifying its population and record landscape.

Across the South Central states, population growth was shaped by agricultural expansion, land speculation, and the spread of railroads. Government documents, church registers, land deeds, and ethnic community records help genealogists trace the transition from frontier outposts to thriving towns and cities. Because each state was settled and administered under different conditions, successful research in this region often requires working across multiple jurisdictions and timeframes—whether you're looking through French notarial archives in New Orleans or searching German-speaking Lutheran baptism records in rural Missouri.

These layers of settlement and sovereignty not only created rich paper trails, they also shaped the cultural fabric of the South Central region. Today, family historians uncover stories of resilience, migration, faith, and transformation in records that reflect the multilingual, multicultural roots of the American experience.

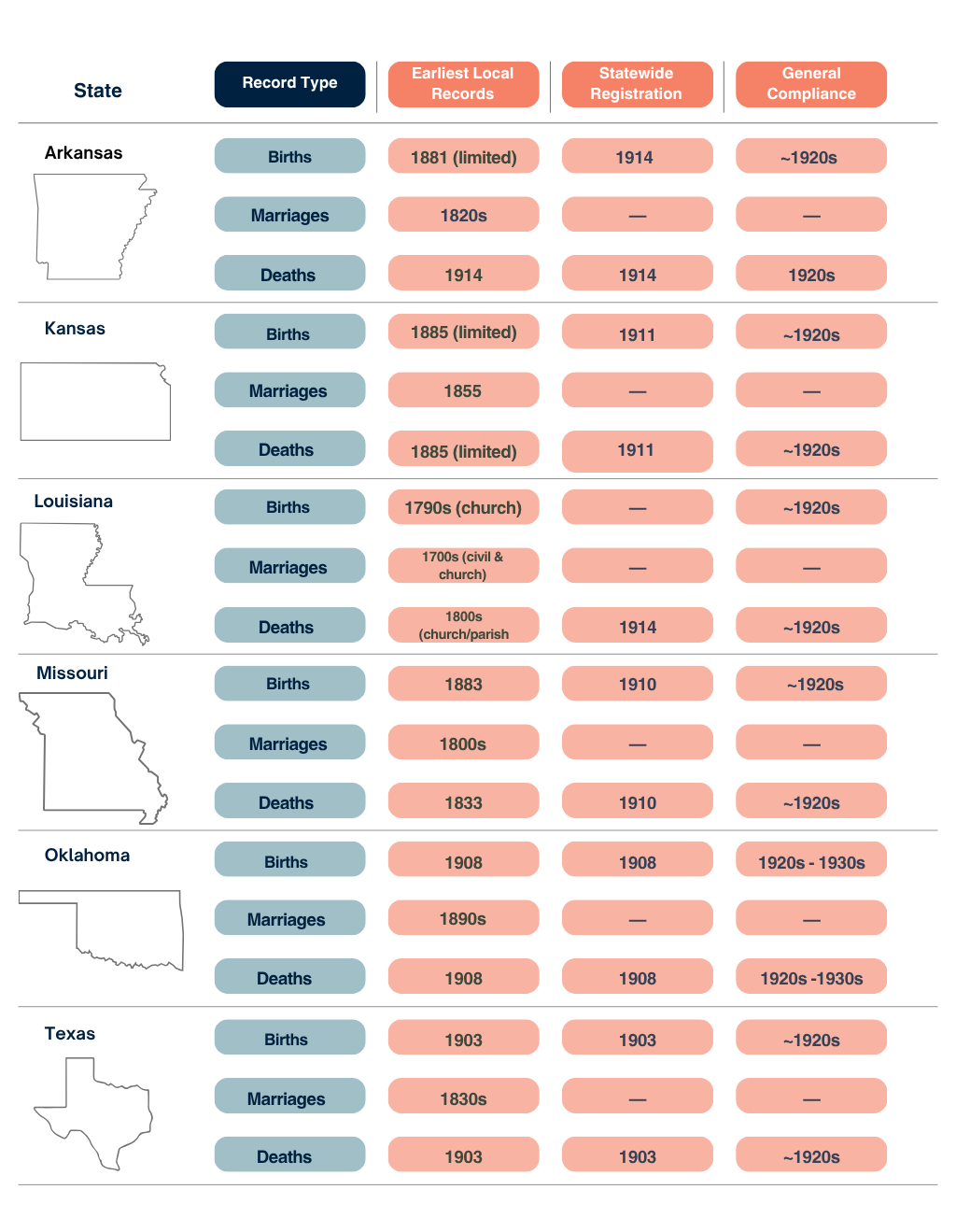

Arkansas was settled early by migrants from the Upper South. Its courthouse records and early state censuses offer a strong foundation for family historians, while Freedmen’s Bureau documents and land claims expand post–Civil War research.

Kansas offers excellent homestead applications, military pension records, and voter registration lists. It’s a key state for researchers tracing African American homesteaders, abolitionists, and pioneers of the Great Plains.

Louisiana is a treasure trove for Catholic sacramental records, French notarial archives, and early civil registrations dating back to the 18th century. Its rich Creole, Acadian, and African American history makes it a cornerstone for Southern genealogical research.

Missouri bridges North and South and offers rich territorial, migration, and war records. Military bounty lands, German immigration registers, and state health reports contribute to a detailed genealogical profile.

Oklahoma's tribal and territorial roots offer unique Native American enrollment files, land allotments, and mixed-race family records. Indian Territory documentation—prior to statehood in 1907—is particularly valuable for Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole lineages.

Texas boasts records in Spanish, English, and German. Catholic mission archives, county deed books, and early Republic files combine to offer one of the most diverse archival environments in the U.S.

Researchers in the South Central states must navigate a mix of colonial legacies, local jurisdictions, and overlapping legal traditions. Many early Catholic, Spanish, and French records are still held by diocesan archives, particularly in Louisiana and Texas. These contain baptisms, marriages, confirmations, and burials with rich generational detail.

County courthouses remain essential for deeds, probate, and marriage licenses. In rural areas, school census records, voter rolls, and church minutes fill in the gaps between census years. In more urban regions like St. Louis, New Orleans, San Antonio, and Kansas City, researchers will find city directories, health records, immigrant assistance files, and Black community newspapers.

African American genealogy in the South Central region is especially robust due to Freedmen’s Bureau documents, plantation inventories, and church burial records. Hispanic and Indigenous lineages are documented through land grant archives, mission conversions, tribal census rolls, and bilingual parish books.

The South Central states offer an unparalleled blend of cultures, languages, and record systems—providing researchers with powerful tools to uncover their family's journey. Whether your ancestors arrived from Europe, moved west from the Appalachians, or lived on these lands for generations, the region holds a mirror to American transformation and diversity.

Whether you're searching in a Spanish mission ledger, a county courthouse, or a Freedmen’s Bureau archive, Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Texas offer a wealth of opportunities for tracing your family story.

Contact Trace today and let us dig into the heart of the South Central states—where ancestry lives on in every land patent, census book, and baptismal record.

Explore these additional research locations and specialty areas: