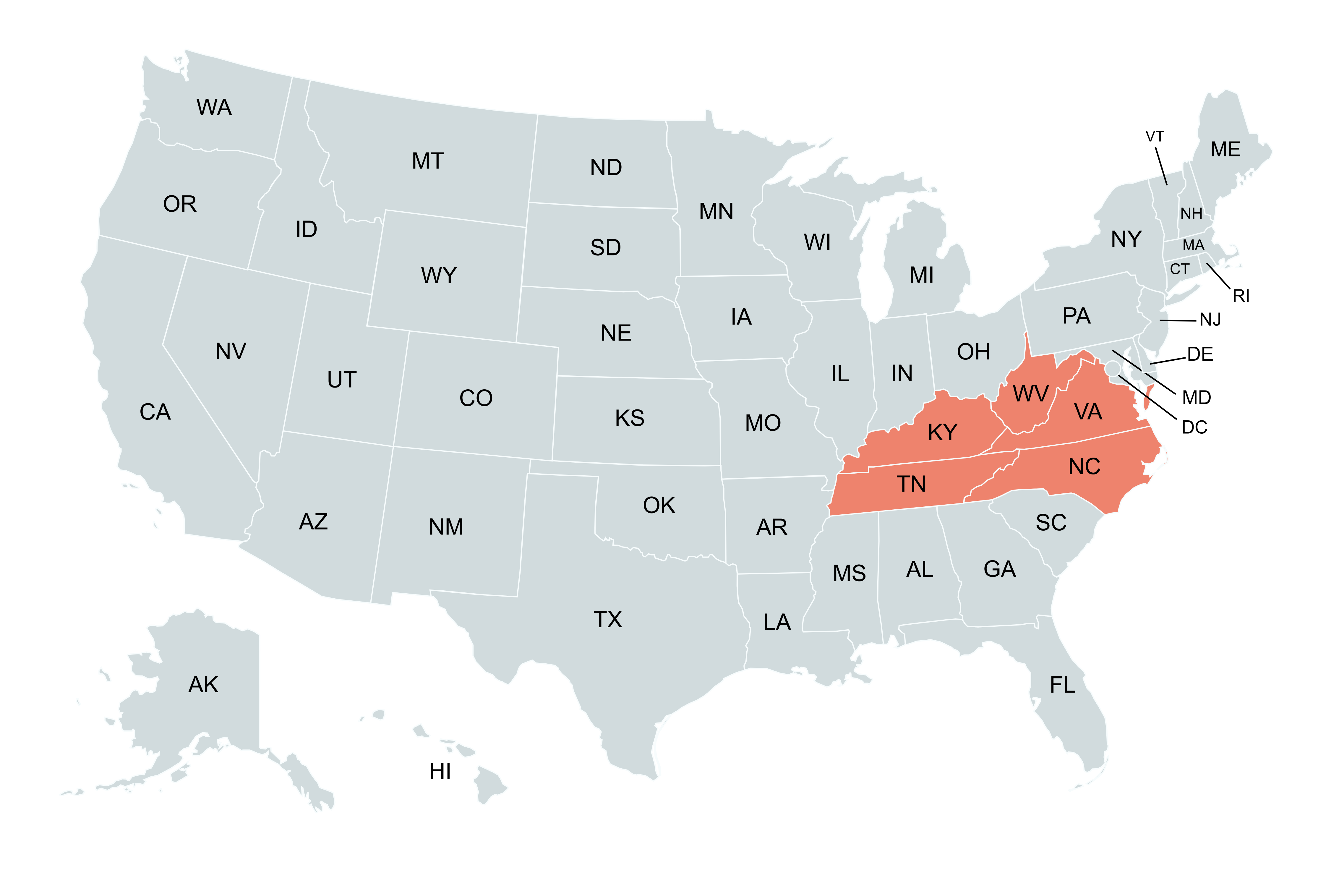

The Upper South, comprising Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, represents a rich genealogical corridor shaped by early American settlement, frontier expansion, Civil War legacy, and Appalachian traditions. From coastal Virginia plantations to Blue Ridge homesteads, this region offers one of the longest timelines of preserved family records in the United States.

Whether your ancestors fought in the Revolution, traveled the Wilderness Road into Kentucky, or worked in West Virginia’s coalfields, the Upper South’s well-maintained civil, church, land, and military records make it an essential area for genealogical discovery.

The story of the Upper South unfolds through the earliest colonial settlements, revolutionary ambitions, frontier exploration, and a deeply complex legacy shaped by slavery, Civil War, and Reconstruction. This region served as both a cradle of the American republic and a corridor through which countless families moved westward into the heart of the continent.

Virginia, founded in 1607 at Jamestown, became the first permanent English colony in North America. From there, the tobacco economy boomed, relying heavily on enslaved labor and establishing an aristocratic plantation culture that would influence its neighboring colonies. The Virginia General Assembly began requiring vital records in church registers as early as the 17th century, and these vestry books and parish records now offer some of the oldest genealogical documentation in the country.

North Carolina emerged as a more rugged frontier, with settlers, often Scots-Irish, German, and English, moving into the Piedmont and Appalachian foothills. The Moravian and Quaker communities in the north and west maintained especially detailed records. Baptismal, burial, and marriage registers in multiple languages (including German and Latin) were routinely kept by church elders and circuit-riding ministers who served dispersed rural populations.

Tennessee began as part of North Carolina’s western frontier, where families crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains into the fertile valleys of East Tennessee. By the time Tennessee achieved statehood in 1796, settlements were flourishing along the Tennessee River, supported by military land grants, militia musters, and early court records.

Kentucky, originally part of Virginia, became its own state in 1792 and attracted settlers following Daniel Boone’s Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap. Pioneers arriving in covered wagons brought their family bibles, established frontier churches, and filed claims in local land offices. Many were Revolutionary War veterans claiming bounty lands, and their descendants left behind detailed probate and property records.

West Virginia’s formation in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, was itself an act of genealogical consequence. Its counties, largely loyal to the Union, split from Confederate Virginia and established their own civil government. Vital records, including those kept before and after secession, reflect this divide and are maintained in both state and local repositories.

Across the Upper South, generational ties were reinforced by migration, religion, and community building. Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian denominations expanded widely, recording membership lists, revival attendees, and even moral conduct reports. Military enlistment records—from the French and Indian War through the Vietnam era—abound in this region, offering detailed personal profiles and pension documentation.

The Upper South was also a key theater of the Civil War, and genealogists will find a deep archive of Confederate and Union service records, prisoner rolls, widow pension claims, and civilian compensation files. Following emancipation, newly freed families began establishing churches, schools, and fraternal organizations whose records reflect the resilience of African American communities through the Reconstruction era and beyond.

For researchers tracing Indigenous ancestry, particularly Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes, records tied to treaties, removals, missionary schools, and tribal rolls offer a complex but rewarding path. The region’s historical crossroads created a multilayered archive of race, faith, conflict, and family, preserved in courthouses, church basements, and the memory of the land itself.

Settlement in the Upper South predates the American Revolution and offers some of the earliest genealogical records in the nation. Virginia and North Carolina were among the original thirteen colonies and began recording land transactions, wills, and parish registers in the 1600s. These records, particularly from Tidewater counties, are crucial for researchers tracing ancestors back to the colonial era.

The Great Wagon Road, a vital migration route through the Shenandoah Valley, brought settlers from Pennsylvania into western Virginia, the Carolinas, and eventually Kentucky and Tennessee. These frontier migrations were often documented through land warrants, militia rosters, and church covenants. The establishment of new counties kept pace with population growth, and each new jurisdiction initiated its own system of recordkeeping.

The region’s complex history of land grants, especially those involving Revolutionary War service, created multiple layers of documentation. Virginia’s land claims extended into Kentucky and were sometimes recorded in both states. Tennessee, formed from North Carolina territory, inherited overlapping jurisdictions, making genealogical research both challenging and rewarding.

Religious groups, including Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, were instrumental in establishing schools and recording community events. Meeting minutes, baptismal registries, and cemetery logs are often preserved in local congregations or denominational archives.

The Civil War had a profound impact on the Upper South. Virginia was the heart of the Confederacy, while Kentucky and West Virginia remained in the Union. The war produced a vast paper trail of enlistment papers, pension files, draft registrations, and casualty reports that remain invaluable to genealogists.

After the war, Reconstruction-era documentation added a new layer of bureaucratic and legal records, especially concerning formerly enslaved individuals. Freedmen’s Bureau archives, labor contracts, and voter registrations in states like Virginia and North Carolina are critical for African American genealogical research.

As the 19th century progressed, railroads, industry, and coal mining reshaped the Appalachian economy. The growth of mining towns in Kentucky and West Virginia created employment rosters, company store ledgers, and union membership lists—records that are often overlooked but rich with family detail.

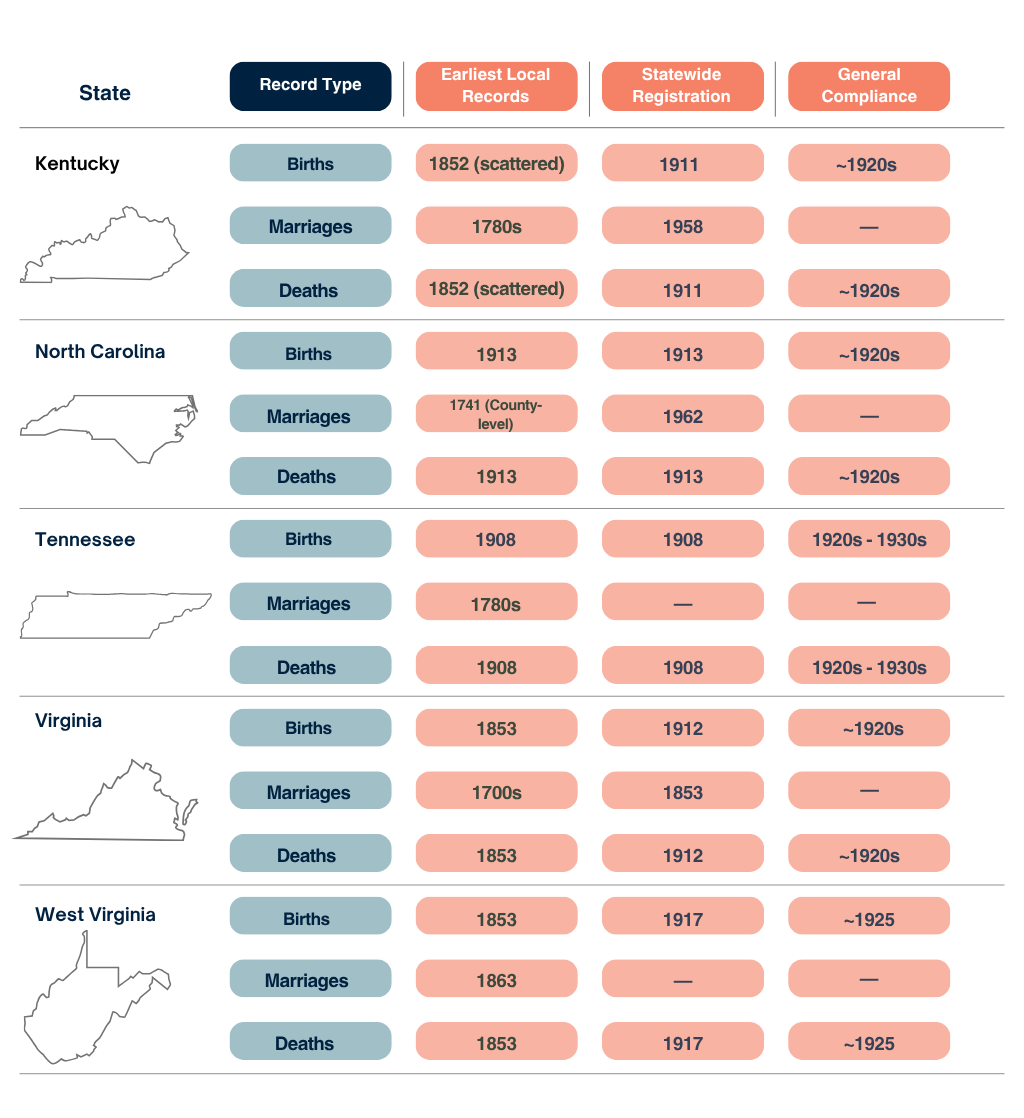

Virginia holds the longest-standing genealogical records in the region. Parish registers, land patents, and chancery court cases from the 1600s offer unmatched depth. The Library of Virginia is a national treasure for researchers.

Kentucky was settled heavily after the Revolutionary War and boasts excellent land grant and military pension files. Its courthouse system is robust, though researchers should be aware of a few notable record losses.

Tennessee is known for strong county archives, family bibles, and church registers. Westward migrations from Virginia and North Carolina are well documented in early land surveys and tax rolls.

North Carolina provides early marriage bonds, colonial land grants, and strong Quaker meeting minutes. It’s also a central hub for African American genealogy due to its preserved Freedmen’s Bureau collections.

West Virginia split from Virginia during the Civil War and has well-organized county records dating back to its formation in 1863. Coal towns, mining unions, and railroad expansions left unique paper trails.

In the Upper South, many of the richest genealogical records are held by county clerks and small-town congregations. Family bibles, cemetery records, and even oral histories are preserved in local historical societies and genealogical groups. Rural churches often hold registers that include births, baptisms, marriages, and deaths—sometimes for entire communities.

Researchers tracing Appalachian roots will find valuable details in land transactions, mining payrolls, tenant farm agreements, and school rosters. Many counties maintain detailed voter rolls, jury lists, and tax digests that can provide missing links in your research.

The Upper South’s family history is woven into the broader American narrative spanning colonial independence, frontier expansion, Civil War transformation, and industrial development. Whether you’re researching enslaved ancestors, Revolutionary soldiers, or Appalachian homesteaders, the region’s records bring those stories to life.

Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia are home to some of the nation’s most vital historical records. Begin your journey today to uncover the legacies left behind in church pews, court ledgers, farmsteads, and battlefields.

Every family has a story. Contact Trace to start tracing yours today!

Take a look at these additional research locations and specialties: